Networked AI Accountability

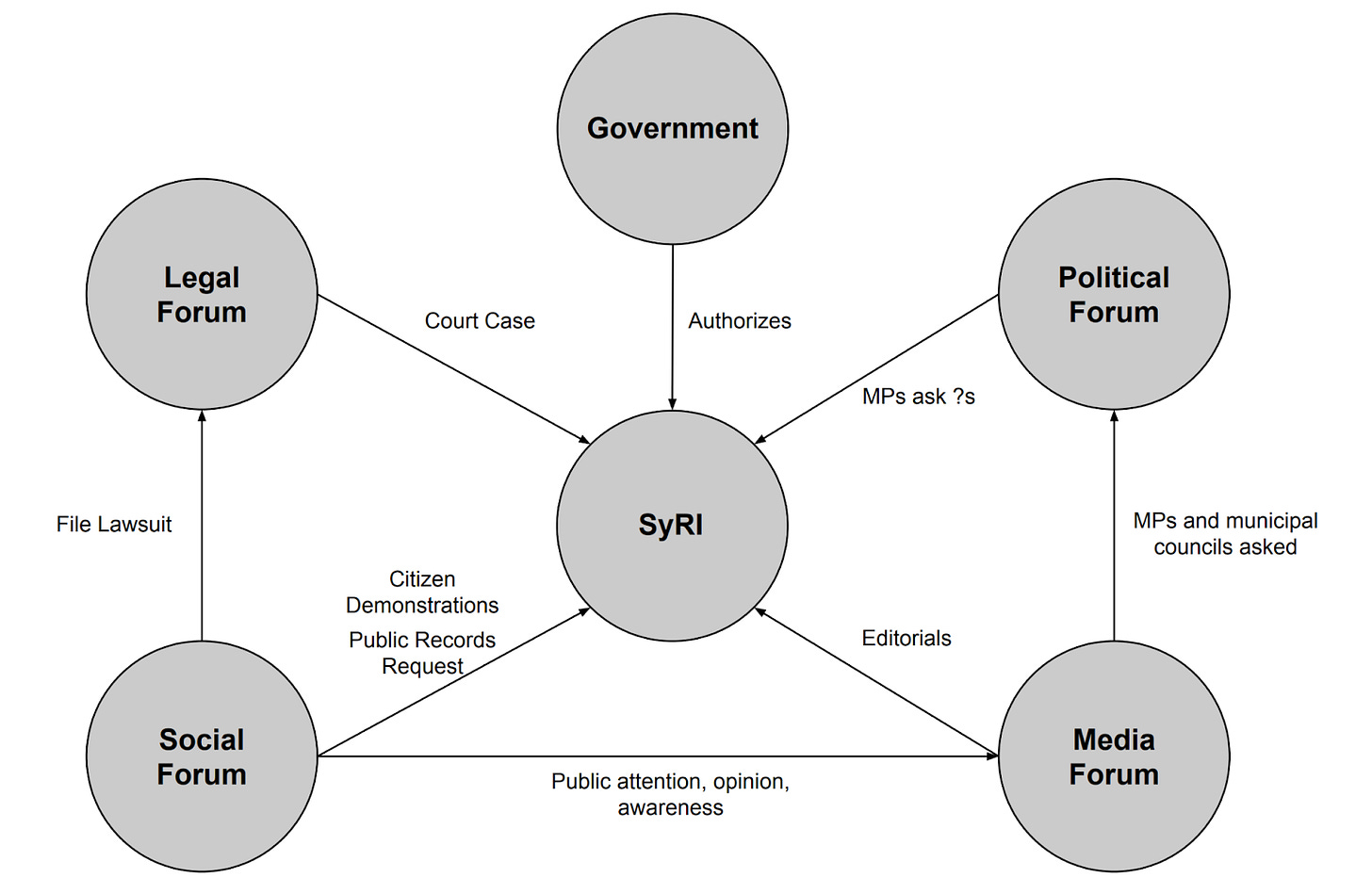

How different forums contributed to producing accountability in the Dutch welfare scandal.

An accountability relationship between an actor and a forum means that the actor has to answer to that forum for some conduct (Bovens, 2007). There are a range of types of forums that might have accountability relationships with AI systems including political (e.g. parliamentary hearings, democratic elections), legal (e.g. courts), administrative (e.g. auditors or inspectors from official agencies), professional (e.g. professional societies, industry working groups), social (e.g. civil society organizations, interest groups), or media (e.g. news media, social media).

Different forums operate in different ways, have different capacities for obtaining information or explanation, and may have different standards of expected behavior or ways to sanction the actor. There are also differences in how their authority is constituted, with legal or administrative authority formally flowing from the state, while professional, social, and media forums gain their authority through other informal social processes. These distinctions correspond to vertical accountability, where a forum formally holds power over the actor often due to a hierarchical relationship between them, and horizontal accountability which is essentially voluntary and where there is no formal obligation to provide an account. Forums can also be public as is the case for political, legal, professional, social, and media forums, while others like administrative forums may be partially public or non-public.

Because of their different capacities to know, act, and sanction, forums often work in concert to hold an actor accountable. In a networked view of accountability the interplay between forums is a necessary feature of how accountability is ultimately rendered (Wieringa, 2020). For instance a forum with informal power and a horizontal relationship to the actor in question (e.g. media) may contribute knowledge that is publicized and which informs a forum with formal power and a vertical relationship (e.g. a relevant governing agency) that can further pursue accountability, if needed in a non-public space that accommodates issues such as trade secrecy or privacy. Different forums respond and react to one another.

Wieringa (2023) provides a detailed description of how networked accountability works, illustrating it with the case of the Dutch welfare fraud system, SyRI (System Risk Indication). Briefly, SyRI was a system implemented by the Dutch government and used by municipalities from 2015-2019 to try to detect potential fraud based on welfare beneficiary data. In 2020 a Dutch court ruled that the law authorizing the creation of SyRI was unlawful because it conflicted with the right to privacy ensured by the European Convention on Human Rights (van Bekkum and Borgesius, 2021). While there had been some administrative forums early in the development leading up to the law which tried to pump the brakes, those forums were ultimately not successful in shaping what became the law before parliament passed it.

How was accountability achieved here? The following figure illustrates many of the various relationships described by Wieringa in the case.

It was ultimately the legal forum that provided the formal accountability and authority to overrule the law authorizing the creation of SyRI. In essence the case was about holding accountable the legislators who delegated authority to create the AI system to risk rate people using private personal information. There were clear limits here though as the legal forum was unable to compel disclosure of detailed information about how the SyRI algorithm actually works, with the government arguing that disclosure of that information could enable fraudsters to game or evade the system (van Bekkum and Borgesius, 2021). As Wieringa (2023) writes, the court indicated that the State “needed to explain how the algorithmic system was designed, tested, applied, and how it operates” but failed to do so. As the court opinion wrote, “[w]ithout insight into the risk indicators and the risk model, or at least without further legal safeguards to compensate for this lack of insight, the SyRI legislations provides insufficient points of reference for the conclusion that by using SyRI the interference with the right to respect for private life is always proportional and therefore necessary…” (Meuwese, 2020). This highlights that even a formal forum such as a courtroom may not be able to bridge knowledge gaps about an AI system, and that insufficient transparency about such systems is a core impediment to accountability.

While the legal forum was able to provide the formal accountability to stop the use of SyRI, both social and media forums also played critical roles in achieving that outcome, and the political forum was further activated in the process as well. Indeed the impetus for the court case originally came from a collection of civil society actors, “The Privacy Coalition”, which in 2016 filed a public records request to find out more about the system (Wieringa, 2023). The critical issue in the public records response was that “crucial information, such as audit reports and PIAs [Privacy Impact Assessments], needed to evaluate the proportionality of the system was withheld”. There simply wasn’t enough information to assess whether the privacy violations at stake might be warranted. In short, the legitimacy of the system couldn’t be established on the basis of the information provided: the state hadn’t provided a sufficient account to the social actor. Unsatisfied with the level of detail provided, The Privacy Coalition then sued the state in 2018, moving into the legal forum.

The lawsuit also stimulated some activity in the political forum, with two ministers of parliament (MPs) filing to make the SyRI system transparent, which was denied by the state. Around this time The Privacy Coalition activated the media forum through a campaign to educate the public about SyRI and shape public attention, opinion, and awareness of the system and the issues it exposed. This had the apparent effect of also stimulating more social actors in the form of citizen demonstrations, which were then covered and amplified by the media further. The media forum also participated by scrutinizing SyRI and developing arguments against it through published editorials and commentaries, and by asking members of parliament or of municipal councils to account for the system.

Accountability is not a clean process. It involves lots of relationships, connections, and back and forth as different forums gain information and trigger or reinforce each other. Forums with informal, horizontal accountability relationships are needed to mobilize information, however at the end of the day there needs to be formal accountability from a forum with the power to change the situation and sanction actors, in this case by overturning a law. That means we need laws that define what AI behavior is permissible (or as in this case, what values like privacy need to be preserved in AI system behavior), and that other forums need to have capabilities to gain knowledge of AI behavior such that they can potentially activate formal accountability in a legal (judicial) forum. To the extent that the state would want to defend or reimplement a system akin to SyRI that system would need to offer more algorithmic transparency to clearly demonstrate how the government interest in efficiency of fraud detection is balanced against relevant fundamental rights.

References

Bekkum M van and Borgesius FZ (2021) Digital welfare fraud detection and the Dutch SyRI judgment. European Journal of Social Security 23(4): 323–340.

Bovens M (2007) Analysing and Assessing Accountability: A Conceptual Framework. European Law Journal 13(4): 447–468.

Meuwese A (2020) Regulating algorithmic decision-making one case at the time: A note on the Dutch “SyRI” judgment. European Review of Digital Administration & Law 1(1).

Wieringa M (2020) What to account for when accounting for algorithms: a systematic literature review on algorithmic accountability. FAT* ’20: Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency: 1–18.

Wieringa M (2023) “Hey SyRI, tell me about algorithmic accountability”: Lessons from a landmark case. Data & Policy 5.