The Problem of AI Accountability

How do we make sociotechnical AI systems answerable for their behavior?

To help set the scope for the AI Accountability Review I want to start us off with a solid definition of AI Accountability and the problems it entails. These can help drive towards potential policy options to address those problems. We’ve got two big ideas intersected here: “AI” and “Accountability”. Let’s dissect what they mean—individually and then together.

Refined over several years, the OECD’s definition of AI System is broad and jargon-heavy, but also precise: “An AI system is a machine-based system that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments. Different AI systems vary in their levels of autonomy and adaptiveness after deployment.” (Explanatory memorandum on the updated OECD definition of an AI system, 2024). Algorithms are formally defined differently than AI, but for the purposes of what accountability means in this context, I view the earlier nomenclature of “algorithmic accountability” (Diakopoulos, 2015) as practically synonymous with “AI accountability” discussed here.

Objectives are the goals of the AI system. They can be explicitly written as rules by people, or they can be implicit in data that encodes examples that the system should emulate, for instance, through machine learning. Inferences are outputs of the AI system created on the basis of inputs. Autonomy is how much a system can act without human involvement. And adaptiveness is the idea that an AI system can evolve after its initial development.

The OECD clarifies that “an AI system’s objective setting and development can always be traced back to a human who originates the AI system development process.” Indeed, it is broadly recognized that AI systems are complex sociotechnical systems that interweave a machine-based component and a range of human actors in their design, development, deployment, and use (Chen and Metcalf, 2024). Human influence is always present even if only indirectly linked to actions an AI system takes. As Novelli and colleagues describe further: “The performance of a sociotechnical system relies on the joint optimization of tools, machinery, infrastructure and technology … on the technical side, and of rules, procedures, metrics, roles, expectations, cultural background, and coordination mechanisms on the social side.” (Novelli et al, 2024).

Accountability has two meanings in the Oxford English dictionary: answerability (i.e. “...liability to...answer for one’s conduct…”), and responsibility. A definition that has gained some traction in the AI literature is from Mark Bovens, who defines it as: “a relationship between an actor and a forum, in which the actor has an obligation to explain and to justify his or her conduct, the forum can pose questions and pass judgment, and the actor may face consequences.” (Bovens, 2007). This emphasizes that accountability is relational — it exists between an actor and a forum. Both the relationship and the obligation from actor to forum must be established under some authority in order to facilitate an explanation or justification of behavior. A goal for AI policymakers should be to understand how to configure authority to create such relationships.

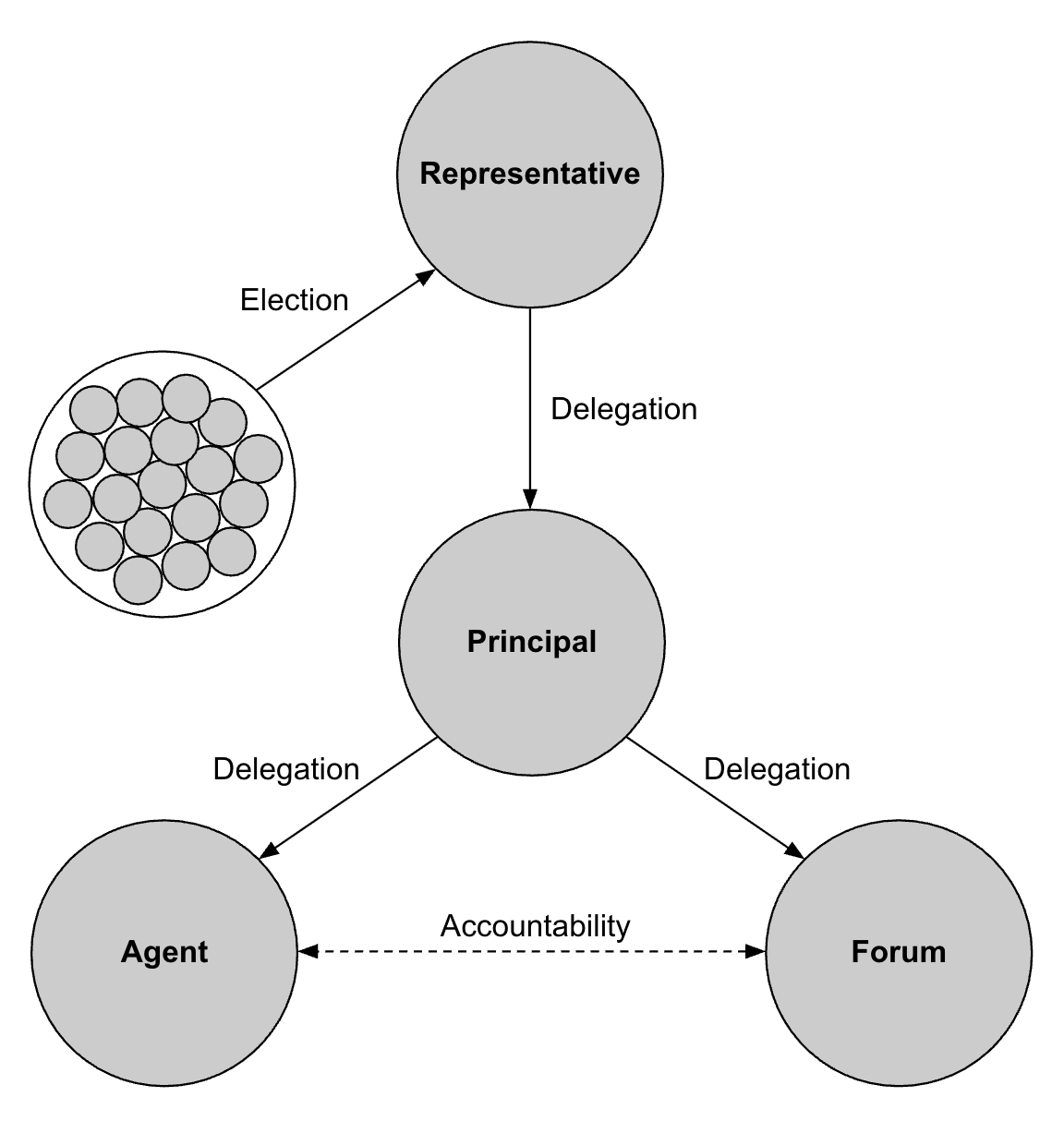

Bovens goes on to write that “Accountability is a form of control, but not all forms of control are accountability mechanisms.” Indeed accountability arises as a response to the problem of delegation in principal-agent relationships where a principal delegates some tasks to an agent which acts on the principal’s behalf. Accountability is the mechanism to constrain this delegation relationship by making the agent answerable to a forum for its conduct (sometimes the forum is just the principal itself). In essence the principal delegates a task to an agent and then monitors the execution of that task, or further delegates this monitoring to a forum which can judge the behavior and enact sanctions if needed. The following diagram illustrates how an accountability relationship is established with authority flowing originally from a democratic election process and where the principal delegates both the task and the monitoring of that task.

Accountability is a mechanism for constraining behavior when delegating to agents that can act with some degree of autonomy. It can help mitigate the risks around the loss of agency by the principal, where the agent’s actions don’t fully align with the principal's interests and goals (Koenig, 2025). No wonder it’s such a fundamental concept for governing AI. If people are going to delegate any number of tasks to AI systems—as they’re now doing en masse with generative AI—accountability is a way for people to manage that delegation. Traditionally accountability has applied to individuals or organizations, but now the agent we’re trying to constrain using accountability is a sociotechnical system where the technical component of that system may have varying levels of autonomy or adaptiveness in the world.

The overarching problem of AI accountability is about how to make sociotechnical AI systems answerable for their behavior. Applying the idea of accountability to AI requires we think through some of the basic dimensions of accountability as per Bovens’ definition, namely: (1) agents that are complex sociotechnical systems, (2) forums that need access to observe and interrogate these systems, (3) the capacity for explanation and justification, and (4) behavioral standards that both trigger accountability, and guide judgements and consequences.

The technical (i.e. “machine-based”) component of an AI system raises issues for assigning moral responsibility. Typically, people are morally responsible for a harm if they caused it and intended to cause it (Nissenbaum, 1994). While AI systems can certainly cause harm, they can’t intend to cause it, although the people in the sociotechnical system certainly could. This alludes to a key question: How should accountability work in a distributed system with complex interactions between human and non-human actors? Issues here relate to distributed responsibility (e.g. organizationally internal vs external, across the supply chain, stakeholder mapping, challenges created by open source, assigning and enforcing sanctions, etc.), moral and legal responsibility (e.g. legal personhood of AI, levels of autonomy/agency/intent, legal liability, etc), human issues (e.g. roles such as user or developer, design of technical artifacts, codes of conduct, human-in-the-loop issues, AI influence on human behavior and vice versa, etc). An underlying issue is in how accountability relationships and obligations are even established to begin with, and with what authority.

There’s also the question of How can forums know about AI system behavior? In order to trigger a request for explanation or justification of conduct a forum first needs to know about that conduct. How do forums observe and monitor complex sociotechnical systems to assess their behavior? This gets into issues of observability and data access, transparency and opacity, measurability, auditing, benchmarking, logging and incident reporting, red teaming, public records laws, and so on. Approaches to knowing about AI system behavior will vary for different kinds of forums, such as political, legal, professional, social, or media.

We also need to grapple with the question of How can AI systems explain and justify their behavior? Once a forum knows about AI system behavior, the system must be able to render an explanation to the forum, which may entail reasoning capability or human-AI interaction to help make sense of how the system took inputs to outputs. This must be done interactively such that the forum can also pose questions, such as to interrogate the system or contest its output. One of the underlying challenges here is how to attribute cause in a complex system, sometimes referred to as the “many hands” problem.

Finally we need a good answer to the issue of What standards should be used to judge AI system behavior? Accountability relies on a set of criteria for assessing behavior, and these could come from social norms and expectations which may differ across actors in the complex system, risk and impact assessment approaches, ethical principles, standards bodies, or regulations. And this all needs to be adaptive as technical capabilities and AI behaviors advance. An open problem is how to agree on standards that might apply around the world to AI systems in global use, not only in what might trigger a call for accountability and establish an obligation from an agent to a particular forum, but also around what the consequences or sanctions should be for behavior that falls short of standards.

In summary, establishing AI accountability is an approach for managing the delegation of tasks to increasingly autonomous and adaptive AI systems. It necessitates addressing fundamental questions about agents as complex sociotechnical systems, enabling forums to monitor and interrogate these systems, ensuring the capacity for explanation and justification, and setting clear behavioral standards for judgment and consequences. Policy approaches will need to address these challenges to create the conditions for AI accountability and effectively govern AI in society.

References

Bovens M (2007) Analysing and Assessing Accountability: A Conceptual Framework. European Law Journal 13(4): 447–468.

Chen BJ and Metcalf J (2024) Explainer: A Sociotechnical Approach to AI Policy. Data & Society.

Diakopoulos N (2015) Algorithmic Accountability: Journalistic investigation of computational power structures. Digital Journalism 3(3): 398–415.

Explanatory memorandum on the updated OECD definition of an AI system. (2024). DOI:https://doi.org/10.1787/623da898-en.

Koenig PD (2025) Attitudes toward artificial intelligence: combining three theoretical perspectives on technology acceptance. AI & SOCIETY 40(3): 1333–1345.

Nissenbaum H (1994) Computing and accountability. Communications of the ACM 37(1): 72–80.

Novelli C, Taddeo M and Floridi L (2024) Accountability in artificial intelligence: what it is and how it works. AI & Society 39(4): 1871–1882.

So we let AI systems plead the 5th? Hmmm. IMO we can’t just talk about a narrow explanation from an ML system, agreed that that will not clarify. But rather we should look at explanations from a systems based perspective, how else could we establish any (however imperfect) narrative of causality? But this also reminds me that I need to write more distinguishing retrospective vs prospective accountability, because prospective accountability doesn’t rely so heavily on explanation…more to come.

Very nice broad summary of key issues. I do wonder though why we need to grapple with the question of how can AI systems explain and justify their behavior. Explanations for decisions and predictions are as suspect coming from an AI system based on machine learning models as they are when given by people. Such introspections are at best guesswork, even if we exclude prevarication. Someone's account of why they did something has ultimately had little value when constructing the causal chains of accountability. Why should it be different for AI?